"This Person Is Too Powerful": Jeff Buckley Doc Slaps and Soars with a Legend

It takes nothing away from what director Amy Berg has accomplished with her (now-streaming) Jeff Buckley documentary to note how strikingly watchable her key subject is in every frame he occupies. There’s a character he steadfastly refuses to play—the budding rock star with a big record deal and studiously applied charisma—but in outmaneuvering that trap he creates a much more interesting persona for us to avidly drink up.

Elfin, wary of eye contact but then suddenly owning the lens from inches away, he’s often sullen of mien but with an inner sweetness that refuses to be wholly crushed. The boy who was raised as Scott Moorhead wears his paternal surname like a curse, and then wholly inhabits his own version of departed father’s knack for a charming sideways smile--and compelling performances.

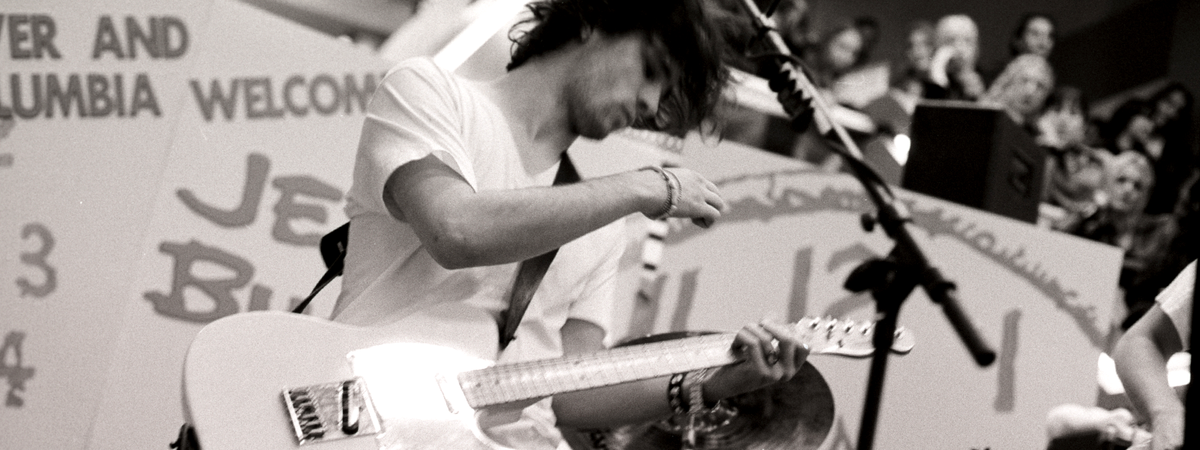

Vocally tip-toeing through the Nina Simone homage that is “Lilac Wine,” or alchemically reinvigorating Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah” with a definitive. billion-downloads version for the ages even as a thousand covers try for the same, he relates mostly to the microphone, eyes wide shut, fingering chords ever so deftly, yet all but absentmindedly:

He was tuned to all frequencies, as one friend points out, so we are not surprised to see the fiery intensity of Jimi Hendrix is hardly more imbued in him than the brave, wounded pathos of Edith Piaf.

Another key set of assets Berg knows how to use wisely alongside her atmospheric mood-setting is the voluminous, mostly selfless good will of her interviewees. They carry all the depth of feeling he inspired, but seem to eschew the potential lingering despair from losing him to a tragically cautionless drowning death in 1997. If the feeling just behind the doc's curtain is “We would have saved him if we could," there are no interrogating judgements as to how he might still be with us. (There is shade directed towards the tenor of Rolling Stone’s—i.e., my own--coverage of his death, as addressed below.)

There’s a banked eroticism in the doc’s portrayal of his love relationships, initially leaning in with initial New York City lover Rebecca Moore. We see her, a gamine and charming, downtown-artsy youth, and then much more in thoughtful adulthood, candid and self-deprecating, all in for the cuddly genius who was taken away. Similarly lucid and sturdy of heart is later girlfriend Joan Wasser. Another muse might have waxed on about her own musical gifts, or worked her own magnetism for the camera--one mutual friend called her impact early on as ‘lots of shiny’—but she opens the curtain to reveal him, as when she’s fondly miffed at her own inability to put up solid resistance: “This person is too powerful.”

Even as he sought a way to isolate himself (and yet fire up a studio full of confreres) with his move to Memphis about a year before his death, he wanted a place to ”really sink into” and ”work my ass off, baby” even as he faced a “deal with the devil,” i.e. mass success. Even as he imported his band, after a lapsed musical foray with Tom Verlaine, a close friend painfully watched him start to “spiral around” his greatest fear, the ”loss of his artistic freedom.”

When Rolling Stone tapped me as the staff writer to dispatch to Memphis to seek an account of just what had happened that night in the Wolf River Channel of the Mississippi River--and fit it somehow into context of hisuntil-then-burgeoning career—my hope was to find a graceful envoi.

My summarizing musical take would be: Buckley had immense self-confidence, a kind of bad-boy zeal mixed with a natural spieler’s stage savvy. He could play, note-perfectly, the ’60s and ’70s rock that he said had “polluted” his musical training. And he immersed himself, courageously, into anything from Edith Piaf and Billie Holiday (he once called himself “a chanteuse with a penis”) to the Bad Brains, Van Morrison and scads of Bob Dylan. He particularly loved Dylan’s “If You See Her, Say Hello.”

I knew the “Grace’ album back to front but had never seen him play downtown at the legendary run of one-off gigs at the club called Sin-e’ (spawning a four-song live EP in 1993). I hadn’t dared to hope for what I found: his cohort was forthcoming, eager to get it right. What had been Elvis Presley’s town was now—in intensity if with a huge difference in scale—had become Jeff’s, at least among a select circle.

The resultant story began:

For Jeff Buckley, it had been an early evening of driving around Memphis, Tenn., in a rented truck with his fellow musician (and roadie) Keith Foti, listening to Foti’s mix tape — Jane’s Addiction, Porno for Pyros, the Beatles’ “I am the Walrus.” Their idea was to eventually go play twin sets of drums at a rehearsal space set aside for Buckley’s band, which would be arriving by plane later that very night of Thursday, May 29, to begin recording the follow-up to his first full-length album, Grace. But Buckley couldn’t seem to locate the building.

So they drove, recalls the 23-year-old Foti, not stopping to eat or drink, until the idea came: “Why don’t we go down by the water?” Around dusk they parked the truck in the nearly empty lot adjoining the Tennessee Welcome Center near the heart of downtown. They brought their boombox down the sloping bank to the shoreline of the Wolf River channel of the Mississippi River.

Within a few minutes, Buckley would be a victim of the river’s noted unpredictability — and his own. Though his friends and the local authorities would spend a long night of fruitless searching, it was presumed that Buckley had drowned. It would be six days before the singer’s body was given up by the river, found at the foot of Beale Street — amid branches and the other debris that typically gathers at a slow-swirling eddy where the channel meets the Mississippi. At the time of his death, Jeff Buckley was six months short of his 31st birthday, and his fans and many critics felt that his promise was as bright as any musician of his generation.

Ten days after Buckley’s body has surfaced, his road manager, Gene Bowen, stands by the riverbank. Looking at the muddy rush of water, he asks, “Why would you even put your toe in that? But it’s typical Jeff. He was a butterfly, you know? He was just like: ‘Go with it.’“

There would be no sight of Buckley until June 4, around 4:30 p.m., when a passenger aboard the riverboat American Queen spotted his body

Also: Rebecca had been his first great love: He finally decamped for good from California to be near her. In the inner fold of Grace‘s sleeve, he acknowledged Rebecca’s father: “P., Thank you for her. Thank you for them all. Bless you for us two. Love, Jeff.”

The road, and the demands of minor but intense rock stardom, undid the romance with Moore. Joan Wasser, violinist and vocalist with Buckley’s sometime support act the Dambuilders, became a frequent companion.

With the public ghost of his father (and a glimmer of Jim Morrison, who died at age 27) shadowing him, it was often rumored that Buckley had been abusing drugs, notably heroin…

The piece cites rumors attributed to Courtney Love’s camp, but then states:

Yet a good dozen friends and colleagues who saw Buckley regularly in recent years insist he was either categorically clean or, at most, may have merely experimented with drugs. “If you’re an addict, you’re an addict,” says Keith Foti, who quit substance abuse two years ago, “and if you’re not, you’re not. Jeff obviously was not.”

… In any event, despite early reports mistakenly saying that the autopsy itself had scotched the drug rumors, final confirmation that Buckley died clean was still pending the Memphis medical examiner’s toxicology report, not completed as of a month after his death.

A crucial, platonic local friend of Jeff’s was Andrea Lisle, who’d taken him to Al Green’s church nearby:

The last time she saw Buckley was about 7:30 on the night he died. “Jeff and Keith [Foti] drove up, and Jeff was so excited,” Lisle recalls. “He’d gone to open a bank account, to get a car; he was going to buy the house he was living in, and he was walking on air about his boys coming in. We’d planned to go to a casino, but he wanted to go play the drums.”

Instead, he went to the river. Standing above the channel 10 days later, Gene Bowen considers it all: “The objective originally was just to go down there and — you know, the sun was setting; it’s beautiful here, with the breeze — and play some music and sing. And then he just wanted to go in.”

“He was unpredictable,” says Keith Foti. “That was the beauty about Jeff. Every moment was an expression.”

That as the final line of the piece as it shipped. Too late to make the printed edition, but in an update that did not end up generating any edits to the online version of the story, posted on June 17, 1997:

An autopsy report from the Shelby County, Tenn.'s medical

examiner's office has listed the death of singer/songwriter Jeff Buckley as accidental drowning. A drug test performed by the coroner came back negative and listed Buckley's

blood alcohol level below that of the legal intoxication level.

Jeff’s last message to mother Mary is played by her for Berg’s camera: “You are a person that fought for their child.”

It’s Joan Wasser’s words that seem to reverberate right alongside: “We were so young.”

--------------------------

Rolling Stone, "River's Edge" (paywall):

https://www.rollingstone.com/feature/jeff-buckley-rivers-edge-75789/

Comments ()