Days of Monsters: "28 Years Later: Bone Temple" and "Frankenstein" Have Some Ideas In Their Head

The monster’s power to sustain fear is incumbent upon its ability to reincarnate itself as an allegory of real anxieties.

The Monster in Theatre History, Michael Chemers

Yep--this isn’t one of those “feel-good” posts. The actual thesis that keeps pushing to the fore is more like this: who needs fictional horrors when you can simply jab the remote and watch the Constitution being disassembled with extreme prejudice in the streets of Minneapolis?

And you can bet a bag of cash that hulking ‘border czar’ Tom Homan being shoved into the aftermath of two ICE rub-out’s of citizens won’t stem the anger. Nor will it create much more than a cosmetic drawdown of the thuggery committed by anonymous, ill-trained, over-militarized and generally beefy incels.

Their two most conspicuous child detentions have mostly being addressed, but can anyone still debate the truism that “the cruelty is the point”?

My friend Dr. David Barnouw, the august Dutch resistance scholar (he edited the Critical Edition of Anne Frank’s diary) cautioned online just this week that the Nazi comparisons only go so far: “Evil is not always Hitler, if only it was that simple."

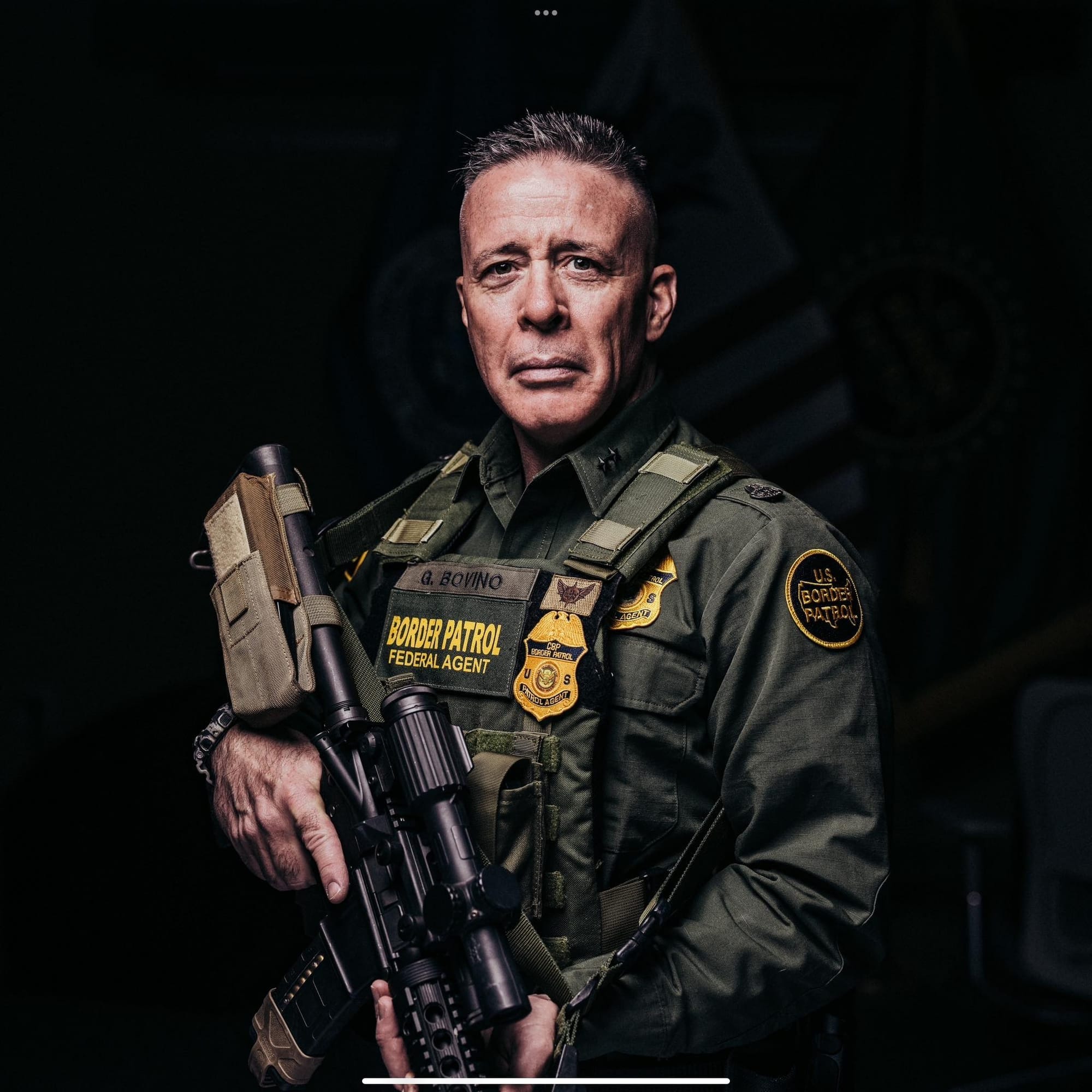

And frankly, the disenfranchisement of the cosplay Border Patrol boss Greg Bovino ( more on him below) takes some of the wind out of such a here-comes-the-next-Reich thesis.

And yet. Before heading towards the pop-cultural matters considered in this piece, I’ll just drop this here from Saul Friedlander’s The Years of Extermination: “On April 6, 1944, Klaus Barbie, chief of the Gestapo in Lyons, informed [obersturmbannfuhrer] Rothke of a particularly successful catch…at the Jewish children’s home…a total of 41 children, aged 3-13, have been caught.”

The brief for both the SS (fanatically Hitlerian racial purity police) and the SA (originally brownshirts, the politicized goon quads) was to serve the party and not strictly the military (the former department handled security only behind the combat front, by contrast to the novel-in-America Trumpian machinery whereby party, military and state apparatuses are conjoined.

Let's table for a moment these horrors of repression and have a look at two films that, per Professor Chemer’s formulation, seize our attention because they get under our skin of our “real anxieties.”

One source of Professor Chemer’s immersion in what’s come to be a robust field of study is found in Jeffrey Jerome Cohen’s 1996 landmark Monster Theory: Reading Culture, where it’s stated, “The monster is an embodiment of a cultural moment –of a time, a feeling, and a place. The monster’s body quite literally incorporates fear, desire, anger and fantasy...”

Certainly the four releases thus far in the 28 films’ array of muck, blood and gruesome dining habits bring on all those elements. The onset of the “infected”, with their sudden and deadly arrival into a too-quiet meadow or at your door, can stoke our not-so-random fears for mankind’s future. In the first of the films, Cillian Murphy’s Jim stood in for us, the terrified audience. With a certain film industry coyness, Murphy appears briefly in the latest…stab at the genre. There's with a coming Jim-centric chapter promised if we the public will just buy some tickets. (That plan by Sony Pictures wobbled a good deal when the two recent ones each saw a second-weekend plunge in attendance.)

Still, the loyal and even fierce fan base established with 2002’s landmark 28 Days Later clung on through 28 Weeks Later (2007), directed by Juan Carlos Fresnadillo, then skipped gaily past the never-to-be notion of twenty-eight months later, and remained eager through two decades to greet 28 Years Later in 2024 with director Danny Boyle again executing the at-points-macabre saga based on another script from Alex Garland, the original creator

Said worthy has been paid much heed by this blog—q.v. with posts about Civil War, last year’s Warfare, and more:

Many of us have lurched upright in their seats to during the films’ terrifying sprints to outrace the giant Alpha who epitomized our terror of being savaged by hordes of “the infected” in the 28 film cycle thus far.

We filmgoers endured similar frights as of mid-October of last year, tasting the dread of being flung like rotten fruit from the decks of an icebound ship early in Guillermo Del Toro’s obsessively crafted Frankenstein.

What the two films have in common, along with the freighted anxiety, is a quiet insistence on making their respective central stories into what at some level are father-son parables. Doctor Ian Kelson’s hulking ‘Samson’ and doctor Victor Frankenstein’s dysmorphic Creature both strain mightily to unite with their guardians over a search for shared human language. (I must say the always-skilled Oscar Isaac won my full empathy, as his struggles to communicate with his otherwise awesome creation foundered early on at the level of, well, me trying to parse whether our family cat wants in or out.)

Mary Shelley authored the original 1819 novel Frankenstein; or the Modern Prometheus as a response to a dare by confrere Lord Byron during a rainy summer rustication. In coming years she was as baffled as anyone to see its cultural power. The key to the drama’s lasting pathos in Del Toro's reconstruction is the loneliness so well rendered by actor Jacob Elordi. As the novel's gaggle of spare parts said as his brain awoke to reach out to his maker, “Remember that I am thy creature; I ought to be thy Adam...I was benevolent and good misery--made me a fiend.”

Elordi was handed the part when Andrew Garfield dropped out with just nine weeks until shooting was to start, and has recently been rewarded with an Oscar nom (though it’s a very long shot) as Best Actor.

Perhaps the most intriguing performance of the 28 bundle hides in plain sight. The still image that sits atop today’s post foregrounds the track-suited and tiara’ed English actor Jack O’Connell, who has been arriving at character-actor-plus stardom for over a decade. (I’m fond of his turn as SAS commando Paddy Mayne in the 2022 BBC streamer “Rogue Heroes.”) When he’s interviewed, O'Connell's vibe is very similar to that of fellow acting stalwart, the Irish Paul Mescal. Each will give you a glimpse of their deep intelligence for ferreting out the meaning in character work, but then waving off praise, as i it's simply something their colleagues mostly enabled--just a larf born out of dumb luck.

O’Connell plays Jimmy Sir Lord Crystal, as a very specific sort of monster. They share a puerile self-glorification, not unlike the wraith who’s pestering us right now in the streets of America, as personified by Border Patrol whack job Greg Bovino. Scroll down to see this him “gorgeously attired” (as a NY Times correspondent depicted Field Marshall Herman Goering in 1939).

If a key element of what monsters can bring on is horror, the other main component Professor Chemers cites from Aristotle’s Poetics is of course pity. Both our non-human figures discussed here earn our pity, deepening out investment. O’Connell knows this in his actor’s bones, and in showing it only amplifies the wonders of Ralph Fiennes’ performance as his canny opposition.

O’Connell’s best particularizing of boss Jimmy’s inner uncertainties arrives when Fiennes’ quietly schools Jimmy as to how far south this cult leader thing has gone. Lord Jimmy's querulous, near-to-pleading eyes show an awareness of the character’s potential plight. (The adult character is of course the same scared kid we saw early on in last year’s iteration, quiveringunder the threat of an infected' assault. In his terror he’ll adopt a phrase probably learned from his dad—a mad cleric ready to embrace the rapture: “Why hast thou forsaken me?” That phrase will reverberate near the current film’s finale.

In what has played out to be a useful branding and creative update The Bone Temple handed the directing job to Nia DaCosta. Having recently won critical favor with the Tessa Thompson-starring Hedda, DaCosta absorbed, then rejiggered Danny Boyle’s cinematic playbook. Her narrative and editing style is as good deal smoother than Boyle’s was in the earlier iterations. She shows us the ineluctable path– one we knew, from the trailer and the fan boy underground telegraph, is on a steady course to where the man of science and the imp of Satan must meet at the titular temple of bones.

The giddily articulate DaCosta has freely owned the amount of sharp-edged gore in her interpretation. “I just love how weird and different The Bone Temple is, “she told THR’s Mikey O’Connell, “I also love how existential and beautiful and hopeful it is alongside all the brutality…that’s what Kelson’s for. He’s an inherently humanist and hopeful character. I think that permeates the film.”

Additionally, the director notes, and monster theory students please note, “You have this zombie thing, which is our fear of ourselves in a really interesting way.”

She’s right of course; but in a world of Noem and Miller and Vance and Bovino, we citizens face a rather more immediate fear. Del Toro, for his part and with the added stakes that he is at some level part of the targeted population, put it this way to IndieWire: “I have all my papers with me at all times and it is a very difficult time when there is no voice for the other. And I think that understanding that the other is you is crucial.

And finally:

Comments ()