Billy Joel: Everybody Loves Him Now

From the New York Daily News Magazine, January 1, 1982:

He asked Elizabeth to manage him in 1976. She'd already sat in quietly in most of the meetings of his carer. A former business student, she'd been seen as harmless. "I was regarded as Bily's girlfriend, a 20-year-old with long hair in a miniskirt." Elizabeth announced herself on the day when Joel's old management called announcing they'd booked him to open for the Beach Boys at Nassau Coliseum for $2,000. It was a hall he could have sold out alone. Says Elizabeth: "I told the guy on the phone, 'Go to hell. You're fired.'"

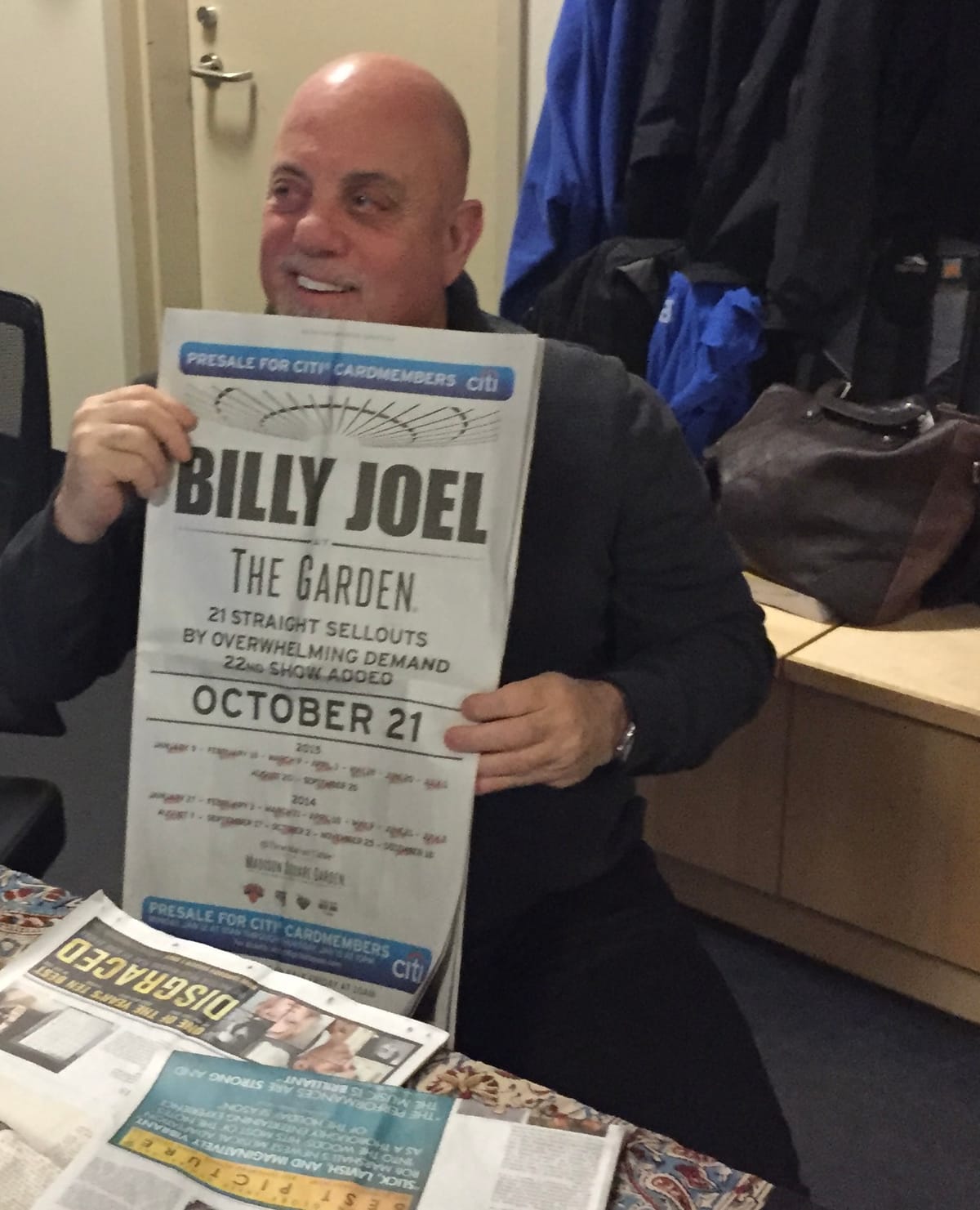

The byline on that article is my own. The text began with a throat-clearing denial of Joel fandom, a “just doing my gig” riff. That attitudinizing haunts me a bit as a present-day Billy Joel fan who ultimately got willing and generous help as his biographer --and now, the chronicler whose blog you just opened up. Even now as the fandom hopes for a successful outcome and return onstage as Billy works to resolve a rare brain disorder, the back-catalog albums , that were once rather recherche' are now (notably "The Stranger" and the "Essential" collection) climbing back into the charts.

Elizabeth always was and always will be an integral part of the story. In my temporary role as Billy's would-be ghostwriter culling info in 2008-2011, I one day found myself walking the beach at Santa Monica with her. Almost at once, as I’d been warned by the man himself, she made it clear that the Joel autobiography he and I were working on would be absent any fresh quotes from her.

She was not one for pleasantries. Nowadays we may call it a transactional personality type. In a clinical but not quite disagreeable way, she let me know the ex-husband’s autobiography, similarly to an earlier "Last Play at Shea" doc, would not be getting any input from her.

Some 16 years later, it would require Executive Producer Steve Cohen's steady charm campaign to convince his longtime good friend Elizabeth to sit with Susan Lacy for her interviews for the HBO doc “And So It Goes.” One outfit Elizabeth wore for her just-right-key-light turn featured, as Lacy has noted with amusement, a jet-black carapace of a jacket studded with perhaps bite-proof, shiny spikes. And deep in the doc's Part 1, even in the midst of what at tines plays like a feminist anthem starring Elizabeth, the at times "maligned" wife/manager is given credit as the half-hidden super-power of a guy who was on his way to 33 hit songs. Effective she was; no mansplaining demurral can deny it. Former band member Richie Cannata—he of the crucially bridging tenor sax solo in "Scenes from an Italian Restaurant"--captures a certain insider’s duality about the subject: "With total respect to her, I'm not going to say I was afraid of her--but I was afraid of her."

Perhaps to speed we doc viewers along, the record execs at the Columbia are treated mostly as anonymous mugs in tinted glasses and loud clothes, even crucial label head Walter Yetnikoff who browbeat original manager Artie Ripp into getting finally paid out of the onerous terms he had set up in the young Billy's initial contract.

Had the documentary been searching for the industry's (no doubt widely disrespectful) attitude towards women seeking power, it might have pursued the most salient item, if only in a question to Elizabeth. How to dispatch for good the whispered canard that she had somehow won career concessions for Billy by inveigling CBS head honcho Walter Yetnikoff (nicknamed Velvel, or "The Wolf') through sexual wiles. (From “Everybbody Loves You Now,” the Billy lyric:” Ah, they all want your white body.”) Not that the slur couldn’t be readily scotched, as Yetnikoff did in great earnest when we met in a diner during my book research, but it rattles in its grave as an emblem of the state of play in the industry then.

The last thing anyone wants re-ginned up sensationalism, which the doc studiously avoids, but in reality the personalities involved did their business in the public eye at a time when the music business and accompanying lifestyle (er, cocaine?) were in a alligator death roll. The sharpest players operated in the nighttime club crawl that followed the noon wake-up and three-martini lunch. As the Rolling Stones anthropologically stated about Manhattan in "Shattered" from 1978's "Some Girls”:

Pride and joy and greed and sex

That's what makes our town the best

Pride and joy and dirty dreams and still surviving on the street

Shadoobie!

One more way station towards a take on the artist in question. When our shared attempt at autobiography was canceled by Billy in March 2012—an oft-told and eventually upbeat story for another time—we were mostly out of touch until I attended a late 2012 showcase for music supervisors and various film and streaming exec's at a Hollywood rock venue. Backstage, the notion to revisit the book as a bio came from Billy almost at once, with his casual postulate that any restrictions on the material I'd gathered would be dropped, and should I sign on to what would now be a biography, "I'll help you out."

As I told Newsday's Glenn Gamboa the week the bio emerged in October 2014, "Billy has a great understanding of what biographies are about, and he has a real respect intellectually for the importance of a biography that was done an arm's length from him."

Further from Glenn's piece: “When they would reach a difficult topic, Schruers says, he would still use the music as a jumping-off point. 'Everyone who knows him well will say he has a lot of forgiveness in him… a graciousness about people in his life. If I were searching for bad stuff about so-and-so, he's probably not going to come up with bad stuff about so-and-so. He's going to have a more enlightened, evolved take on those things.'”

Long story short, while at first glance the below may resemble a deeper dive into bad-stuff-that-happened-to-Billy, it's more about that survival the Stones cite, a fighter's journey steep odds; call these recalls a compact selection of pop star parables.

The insights and text (some sourced from previously unused sessions)—will arrive chronologically in upcoming blog posts on Dogtown.

First up is Jon Small’s take on the broken triangle of his best friend Billy and Jon's wife Elizabeth falling in love and fleeing the emotional impact for a new life in Los Angeles:

From “Billy Joel: The Definitive Biography” (and its research files):

The disruption in all their lives came partly out of youthful naivete, and was hardly made less anguished by the tanked sonic experiment that was the near-psychotic heavy metal album effort, Attila:

As Jon admits, "We sucked in the studio, and in the six or so gigs we ever played live. But the bond that grew between us as we were going through the low points probably equipped us for a friendship that would stand the test of time." Time was far from the only test the friendship would see. The signal challenge for the comradeship would see the two men sharing an ex-wife, Harry Weber's sister Elizabeth. Jon and Elizabeth had married abruptly not long into their relationship, shortly before Billy joined the Hassles, when she became pregnant with their son Sean. (Sean can be seen, at age nine, on the cover of 1976's Turnstiles, at Billy's elbow amid various crowded-in extras.) The history of the love triangle emerges straightforwardly, in the present day, from the two male principals. In fact, the two men, insiders say, still compare notes on their shared ex—Did you have to go through this too? But at the time when the partners were changed, and in several tumultuous years afterward, the relationship would be wrenchingly emotional. Jon remembers one crucial twist. "This is the part where it gets a little squirrely for me," he says. "We were a bunch of hippies. That's what we really were.

And [in 1970] we moved into one house together, in Dix Hills. It was all stone and cement, so we'd end up naming it the Rock House. And it was me, Elizabeth, and Billy." Prior to that, the trio had been living in the Fairhaven Apartments near Billy's old street in Hicksville—Jon and Elizabeth in one apartment, with Billy across the hall. At the same time, Jon ranged about Long Island's clubs seeking out gigs, while Billy worked occasional odd jobs. Says Jon: "What happened is real simple—he just fell in love with my wife. That's it. And when I found out, our friendship was over."

In fact, the bond between Billy and Jon would ultimately survive. But Billy's fascination with Elizabeth was inescapable, partly based on her indefinability: "She was—different. She wasn't like a lot of the other girls I knew at that time who had taken home ec and cooking classes. She was a very bright woman, and she wasn't afraid to show how smart she was. I suppose that made her kind of exotic. Intelligent and not afraid to speak her mind, but could also be seductive. Almost like a European type—not a typical American girl."

Official video promo fo the song from "Cold Spring Harbor"

The situation reached its breaking point one day when Billy and Jon were doing one of the rare gigs they played as Attila—two shows, both sold out, at a club in Amityville. "So we played the first set," remembers Jon, and "and we went over great. "Billy never perspired, but when I'd go in the dressing room, I'd be soaking wet. I used to use an Electrolux vacuum cleaner to blow-dry my hair, because there were no blow dryers back then. So I had this big vacuum cleaner going, holding it up. I'm looking out the window, and there are Elizabeth and Billy talking. "The next thing I see is that Billy's getting in the car with her and leaving. But we still have another show to do. I get dressed as fast as I can, jump in my car, and I know they're going back to the Rock House … and there they were..."